I originally wrote this as a unit of work to go with ISAs, which were the way that practical work was assessed on the 2009 specification. I think I now have an idea what the 2016 specification is after, and have rewritten this project to reflect the changes, hopefully I am not too far from what the examiners are thinking.

Tag Archives: education

AfL, Feedback and the low-stakes testing effect

Assessment for Learning is never far from a UK teacher’s mind. We all know of the “purple pen of pain” madness that SLTs can impose in the hope that their feedback method will realise AfL’s potential and, most importantly, satisfy the inspectors.

I’ve read a couple of posts recently wondering why AfL has failed to deliver on the big improvements that its authors hoped for. AfL’s authors themselves said:

if the substantial rewards promised by the evidence are to be secured, each teacher must find his or her own ways of incorporating the lessons and ideas that are set out above into his or her own patterns of classroom work. Even with optimum training and support, such a process will take time.

but it has now been 20 years since Black and Wiliam wrote those words in “Inside the Black Box” and formative feedback has been a big push in UK schools ever since.

The usual assumption is that we have still not got formative assessment correct. An example of this can be found in the recent work of eminent science teachers who have blogged about how formative assessment is not straightforward in science. Adam Boxer started the series with an assessment of AfL’s failure to deliver, and his has been followed by thoughtful pieces about assessment and planning in science teaching.

Thinking about AfL brought me back to the concerns I expressed here about the supposedly huge benefits from feedback and made me realise that I’ve never looked at any of the underlying evidence for feedback’s efficacy.

The obvious starting place was Black and Wiliam’s research review which had an entire issue of “Assessment in Education” devoted to it:

Black had moved from a Physics background into education research, and had a specific interest in designing courses that had formative processes built into their assessment scheme. Courses and ideas which were wiped out by the evolution of GCSEs in the 1990s. As they put it “as part of this effort to re-assert the importance of formative assessment” Black and Wiliam were commissioned to conduct a review of the research on formative assessment, and they used their experience of working with teachers to write “Inside the Black Box” for a wider audience.

I have to wonder, would someone else looking at the same research, without “formative assessment” as their commissioned topic arrive at the same conclusions?

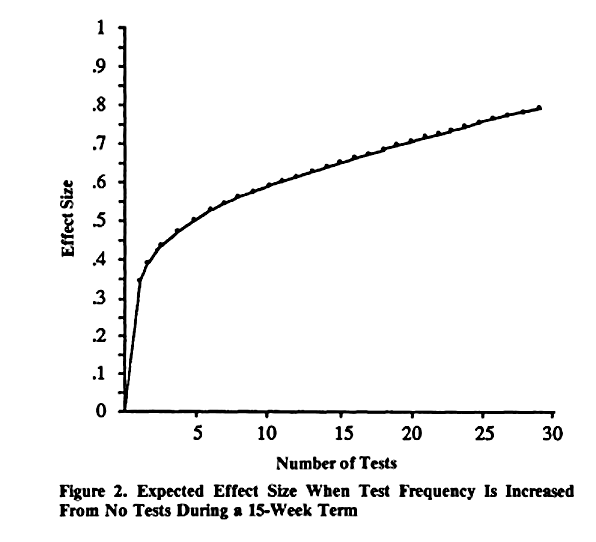

Would some one else instead conclude that “frequent low-stakes testing is very effective” was the important finding of the research on feedback literature? Certainly testing frequency’s importance is clear to the authors who Black and Wiliam cite. In fact one of the B-D and Kuliks papers is entitled “Effects of Frequent Classroom Testing” and contains this graph:

Which is a regression fit of the effect sizes that they found for different test frequencies.

Which is a regression fit of the effect sizes that they found for different test frequencies.

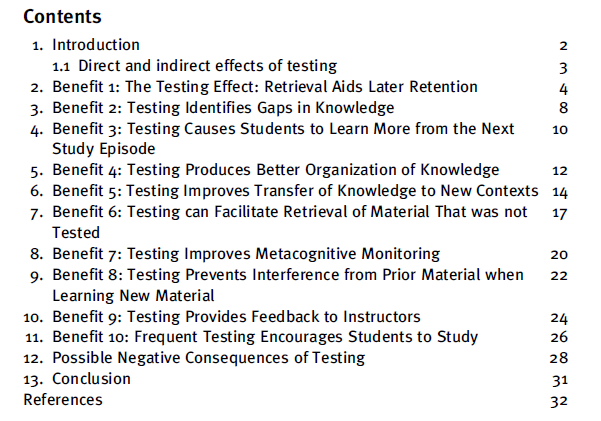

The low-stakes testing effect was pretty well established then, it is very well established now, for example just the contents of “Ten Benefits of Testing and Their Applications to Educational Practice” makes the benefits pretty clear:

Where would we be today if Black and Wiliam had promoted low-stakes testing twenty years ago rather than formative assessment? Quite possibly nothing would have changed, they themselves profess to be puzzled as to why they had such a big impact, maybe formative assessment was just in tune with the zeitgeist of the time and if it were not Black and Wiliam it would have been someone else. But just possibly, if my interpretation is correct – without the testing effect the evidence for feedback is pretty weak -, we might be further on than we are right now.

What I’ve Learnt 2 – Research and Learning

In my last post I argued that much of what teachers believe or are asked to believe stem from Theories of Learning that are not constrained by that pesky thing that scientists insist on: “evidence”.

So what evidence is there, and what does it tell us? Unfortunately it tells us distressingly little.

While I was thinking about how to structure this post Matt Perks (@dodiscimus) tweeted a link to a blog from Professor Paul Kirschner (@P_A_Kirschner):

Kirschner is one of the more famous educational psychology researchers amongst tweeting teachers for two reasons. One, because through his blogs and tweets he gets involved, and two, because of the relentless championing of one of his papers by teacher twitteratti bad boy Greg Ashman (@greg_ashman). Anyway this blog is Kirschner’s attempt to put together a list of “know the masters” papers for those starting out in educational psychology research. As @dodiscimus indicated it is not a short list, but what it does illustrate is the diversity of ideas that have informed psychologists’ thinking about learning. Gary Davis has described has described research into learning as “Pre-paradigmatic”, and while I know that Kirschner wasn’t aiming at a list that described educational psychology as it is today, you certainly don’t get the feeling from his list of masterworks that there is an overarching body of ideas that could be called a paradigm.

With no single paradigm to guide the design of experiments how do you approach finding and using evidence within the field of learning? There seem to be a number of responses to the problem:

Argue that humans are unique and chaotic and that therefore the ideas like “falsification” from the Physical Science simply don’t apply.

Dylan Wiliam (famous in teacher circles for his association with AfL – which is rarely questioned as anything other than a thoroughly good thing, and because like Kirschner he is willing to interact with teachers) has said at least once of education interventions that “Everything works somewhere and nothing works everywhere“. He went on to say it is the “why” behind this that is interesting, which is of course a reasonable scientific position, but it is the “Nothing Works Everywhere” bit that gets quoted with approval.

When I see “Nothing Works Everywhere” being quoted it tends to lead me into twitter spats, because I regard it as a dismissal of the scientific method and can’t help myself. However, I do think that very many teachers sincerely believe that all pupils are unique and that therefore there cannot be an approach to teaching or learning that is inherently better than another. That doesn’t mean that those teachers can not regard themselves as “research informed”, it is just that their research and its implementation are peculiar to them with little expectation of general applicability.

Forget Theory and Investigate “What Works”

If you believe in science does have something general to say about teaching, and moreover if you believe that it is extremely unlikely that evolution has endowed us all with utterly unalike brain architectures for learning, then you probably believe there are some ideas that work pretty much all of the time. This, of course, is what we want in order to practice as “research informed” teachers – some generally applicable ideas that work. It is just that finding them and demonstrating their general applicability is incredibly hard to do; humans are unique and chaotic etc etc.

How can you do it? Well ideally you do it on a massive scale so that when you say that the small effect size you have identified is significant the numbers mean that it probably really is. Unfortunately to conduct that kind of research requires government backing to tinker with education. I only know of one such and that is “Project Follow Through“, although governments can provide researchers with quasi-experiments by changing their education systems. For example, we all wait with bated-breath to find out what the result of Finland’s new emphasis on “generic competences and work across school” – or as the headlines have it “Scrapping Subject Teaching” will be. Unfortunately changes that weren’t designed as experiments have a tendency to be controversial and open to interpretation, probably because the results are so politically charged.

Project Follow Through found that highly scripted lessons with a lot of scripted teacher/pupil interaction worked best for the Primary School age kids in the programme and that the other approaches like promoting self-esteem and supporting parents, improved self-esteem, but not academic competence. How many of us are signing up to do our lessons from a script? I’m not. I am really not that committed to being research informed!

Alternatively, you can simulate a large scale experiment by combining the effect sizes of multiple small scale experiments testing the same ideas; meta-analysis. Most famously this was done by John Hattie in his 2008 book Visible Learning who combined meta-analyses within broad teaching ideas like “feedback” into a single effect size for each. “Fantastic” said many of us, including me, when this appeared, now we know – Feedback/good (0.73), Ability grouping/not so good (0.12), Piagetian Programs/great (1.28).

Unfortunately, Hattie’s results are hard to use. For example, what feedback is good feedback? We all give feedback, so it’s an effect size of 0.73 compared with never telling the kids how they’re doing? Who does that? Or is there some special feedback, perhaps with multi-coloured pens, that’s really, really good? The EEF found this to be a problem when they ran a pilot scheme in a set of primaries “The estimated impact findings showed no difference between the intervention schools and the other primary schools in Bexley” “Many teachers found it difficult to understand the academic research papers which set out the principles of effective feedback and distinguished between different types of feedback” “Some teachers initially believed that the programme was unnecessary as they already used feedback effectively.”

Or take Piagetian Programs – what are they? Matt Perks did some investigation and found that at least some of the meta-analyses that Hattie included in this category were actually correlational, i.e. kids who scored highly on tests designed to measure Piagetian things like abstract reasoning did well at school. Well duh, but how does that help?

So Hattie’s meta-analysis of meta-analyses is too abstracted from actual teaching to be really useful. Many other meta-analyses are open to contradiction, which leads to the question, are there any that are uncontroversial and tell us something useful? Well yes. The very narrow “How to Study” or Revision field of learning does seem to throw up consistent results, as summarised in the work of John Dunlosky. Forcing yourself to try and recall learning helps you recall it later whether you succeeded or not (low stakes testing), and spacing learning out is better than massed practice. A group of academics calling themselves the “Learning Scientists” do a great job of getting these results out to teachers. However, even they find that just two results don’t make for an interesting and regular blog and so stray into blogging on research that is much less certain.

Finally in “What Works”, if you can’t go massive, and you don’t trust metas, then you need to conduct a randomised and controlled trial (RCT) where the intervention group and the control group have been randomly assigned, but in such a way that both groups have similar starting characteristics. It is RCTs that the EEF have been funding as “Effectiveness Trials” and the results have so far been disappointing. I’m sure that some of my disappointment is because I have been conditioned by Hattie to expect big effect sizes. Obviously most of the effect sizes Hattie included were for post-intervention verses the starting condition, rather than post-intervention verses control, and therefore bound to be bigger. However, even allowing for that, the EEF doesn’t seem to have found much that is any better than normal practice. My biggest disappointment was “Let’s Think Secondary Science” which was a modernisation of CASE (Cognitive Acceleration through Science Education). At the 2016 ASE conference in January, those involved were very upbeat about their results so the assessment in August that said “This evaluation provided no evidence that Let’s Think Secondary Science had an impact on science attainment” was a real surprise. However, it was in line with many other EEF findings which tend to conclude that the teachers thought the intervention was excellent, but the outcomes were less convincing. This is even true for some of the studies that are trumpeted as successes like “Philosophy for Children” where the positives are very qualified, for example; “Results on the Cognitive Abilities Test (CAT) showed mixed results. Pupils who started the programme in Year 5 showed a positive impact, but those who started in Year 4 showed no evidence of benefit.”

Go back to Theory

As I see it the final option, the one that I see most often being reported, and to my mind the one that ResearchEd promotes, is to do what I said most of us do, in my previous blog, adopt a theory. Of course any principled educator/scientist is going to pick a theory which they believe has solid evidence behind it, but if you pay any attention to science at all you’ll know that Psychology has a massive reproducibility issue. Therefore if you’ve picked on an evidence backed piece of psychology theory to hang your teaching or possibly your research career around, you know there is a risk that that evidence is far from sound. But don’t let that stop you from being dogmatic about it!

What I’ve Learnt – 1 Theories of Learning

I’ve been a Physics teacher for ten years and head of one of the school’s more successful subjects for the majority of that time. Not having done a PGCE means that I’ve had to work a lot out for myself – when I started I didn’t even know what pedagogy meant. These days I’m confident that I’m reasonably well informed, so what have I learned? I’ll start with theories of learning – in a nutshell – I don’t think there is much science behind them, but we all use them.

Before becoming a teacher I’d done a few jobs including post-doc scientist and zoo tour guide. Coming to teaching late I didn’t do the traditional PGCE – supposedly I was on a Graduate Training Course, but the truth is I was just bunged into a classroom and told to get on with it. In my first year I was evenly split between Maths, Chemistry and Physics. I’ve taught others since, but have concentrated on Physics.

The result of all of this was that I was the most reactionary teacher you’ve ever met, my only experience of teaching before I joined a pretty traditional school was my own grammar school twenty years earlier! You know that progressive/traditional debate – well I didn’t know there was any way except the traditional.

Having survived my first experiences of teaching I was struggling to reconcile my experience in the classroom with CPD that continually exhorted me to organise group work and get the kids to discuss and debate the subject. I realised that I’d best learn something about teaching theory – I had been a scientist after all.

So how do you conduct research? You start with a literature review.

Oh my goodness the literature. It isn’t like scientific literature at all; the continual name dropping and referencing within the text, the asides to sociological theory and the failure to ever use a short word when a longer one is available. I couldn’t make my mind up; was this stuff incredibly profound, and I was just too ignorant to understand it, or was it was really as thin on ideas as it seemed.

I’m still not sure which it is, but I know from other blogs that I’m not the only one to have reacted this way. See for example Gary Davies, the third section of this blog is titled “Education research papers are too long and badly written”!

There were some ideas, however, so what were they?

- Knowledge is constructed by each individual (Piaget)

- The construction of Knowledge occurs socially (Vygotsky)

- Knowledge is constructed only from the subjective interpretation of an individual’s active experience (von Glaserfeld)

- Knowledge is an individual’s or a society’s and is therefore relative not absolute.

- That the brain develops through stages and that the onset of abstract reasoning is not until the teens. (Piaget)

- That skills are more desirable educational outcomes than knowledge (Bloom)

- That the way to learn skills is to ape the behaviour of experts (in Science Education I blame Nuffield).

These are clearly based on theories about the way that learning operates, and so seem like science. But they’re not. To my mind the process runs the wrong way around. By which I mean that it is the theory that is all important, rather than the process of obtaining evidence for or against the theory, as is the case in the Physical Sciences. In Physics similar accusations of “not being scientific” have been made against String Theorists, but I doubt that there is String Theorist anywhere who is not aware of the problem – they organise conferences to discuss it – Educationalists seem utterly unaware or unconcerned.

In fact there is only one of the above about which there seems to be any consensus at all about evidence; the fifth. The Edu-twitteratti would have it that the evidence is completely against developmental stages. Which is a shame because it is the only one I liked! Number five seemed to me to have explanatory power for what I was seeing in the classroom. In fact, authors that science teachers still swear by, Driver or Shayer for example, took a position when they were writing in the Eighties where 5 was accepted as truth.

When I looked into why 5 was so completely ruled out, I discovered that research, mostly centred on tracking babies’ eyes, has shown to everyone’s satisfaction that Piaget massively underestimated what babies can do cognitively when defining the earliest of his stages. How this is a killer blow for abstract reasoning being a teenage onset thing I’m not sure, but I guess it is another example of theory being king – reject one small portion of a theory – reject the theory.

I also suspect another reason for developmental stages being out of fashion: Piaget’s implication that children are cognitively limited doesn’t chime with what most educators want to believe, so 5 is gone.

What about the rest? Well it doesn’t take a genius to realise that if theories 1 through 4 dominate educational thought, then students discovering things for themselves (1&3), in groups (2), without a teacher acting as an authority figure declaiming the truth (4) is the ideal model for how learning should operate. No wonder I was continually being exhorted to organise group work. Meanwhile 6 & 7 explained all that emphasis that a science teacher is supposed to put on investigations and on “How Science Works”. Students need to learn “scientific literacy” not the facts of science.

When you think about it, it is quite liberating to do theory driven education. Pick a theory you like, it doesn’t have to be one of the seven above, it can be anything with a touch of logical consistency about it and at least one obscure journal paper as “evidence”. Remodel your teaching to suit, develop materials, convert your fellow teachers and no doubt your passion will mean that your outcomes improve. Before you know it you’re a consultant, write a book, write two, market a system, save the world!

It is also quite hard to teach without a theory, how do you proceed if you have no idea how knowledge can be inculcated? I suspect, consciously or not, that we all have an idea (maybe it is not fleshed out into a full blown theory) about how learning and the development of knowledge occurs, and we teach accordingly.

So I’ve been at this ten years, what is my unscientific theory of learning?

It is sort of Piaget and runs…

- We carry within us a model of how we think the world works, any new knowledge has to be consistent with that model.

- The most likely fate for knowledge that is inconsistent with the existing model is its rejection, perhaps with lip service being paid to pacify the teacher. Only very rarely will the model be adapted to match the new knowledge

- Knowledge is individually constructed upon the existing model, but the “experience” of the new knowledge can be reading, watching or hearing, it need not be physically experienced or discovered.

- Oh and I’m a scientist so there is such a thing as objective truth, most knowledge is not relative.

Am I prepared to defend this theory – yes. Do I secretly still think that abstract reasoning is a teenage phenomenon – yeah secretly. Do I believe my theory is true – I hope it contains grains of truth, but as a good scientist I have to admit it might be complete nonsense.

Am I somewhat ashamed to be found to be holding views unsupported by science – yes, but if I’ve learnt anything from reading Piaget it is that kids will defend utterly ridiculous theories of how the world works and will fight to maintain the logical consistency of those theories while flying in the face of facts – as adults I imagine we are just better at disguising the process.